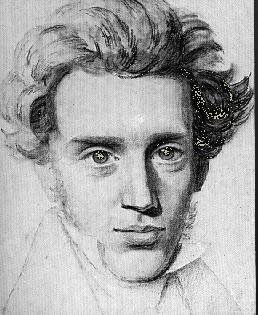

The Melancholy Dane

Today marks the 150th anniversary of the death of the Danish Christian thinker Søren Kierkegaard. Few other writers have captured my heart or my mind more than this one. For the ten years that I have been reading, writing and thinking about “the melancholy Dane” he has consistently reminded me that authentic Christianity is not merely a matter of assent to a certain set of propositions or a matter of merely being a decent fellow but is instead a life of deep passion and a life of radical obedience. To be sure, I have often preferred doctrinal acquiescence and shallow moralisms, but Kierkegaard has kept me from ever feeling okay about that.

Kierkegaard saw himself as a sort of missionary whose task it was “to reintroduce Christianity to Christendom.” He lived in a country that touted itself as being a Christian nation, but Kierkegaard was convinced that in a nation where everyone thought themselves to be Christian, true Christianity did not exist. He writes: “We have what one might call a complete inventory of church buildings, bells, organs, pews, altars, pulpits, offering plates, and so on. But when Christianity does not exist, this inventory, so far from being an advantage, is a peril, because it is so very likely to give rise to the false impression that we must have Christianity, too…. Christ requires followers and defines precisely what he means by this. They are to be salt, willing to be sacrificed. But to be salt and to be sacrificed is not something that the thousands naturally go for, still less millions, or (still less!) countries, kingdoms, states, and (absolutely not!) the whole world. On the other hand, if it is a question of size, mediocrity, and lots of talk, then the possibility of the thing begins; then bring on the thousands, increase them to the millions – no, go forth and make the world Christian.

“The New Testament alone, not numbers, settles what Christianity is, leaving it to eternity to pass judgment on us. It is simply impossible to define faith on the basis of what people in general like best and prefer to call Christianity. As soon as we do this, Christianity is automatically done away with. There are, in the end, only two ways open to us: to honestly and honorably make admission of how far we are from the Christianity of the New Testament, or to perform skillful tricks to conceal the true situation, tricks to conjure up a forgery whereby Christianity is the prevailing religion in the land” (Provocations: The Spiritual Writings of Kierkegaard, 178-180).

It seems to me that these words have not lost there sting, even 150 years later and on an altogether different continent. We, as evangelicals in America today, have much to learn from this nineteenth century Danish Lutheran. And on a much more personal level (as SK would insist we consider his words), I recognize that I still have much to learn about my own pursuit of Christ. Above my desk hangs the following quote that provides me much needed perspective on my work as a scholar and a disciple:

“The matter is quite simple. The Bible is very easy to understand. But we Christians are a bunch of scheming swindlers. We pretend to be unable to understand it because we know very well that the minute we understand we are obliged to act accordingly. Take any words in the New Testament and forget everything except pledging yourself to act accordingly. My God, you will say, if I did that my whole life would be ruined. How would I ever get on in the world?

“Herein lies the real place of Christian scholarship. Christian scholarship is the Church’s prodigious invention to defend itself against the Bible, to ensure that we can continue to be good Christians without the Bible coming too close. Oh, priceless scholarship, what would we do without you?” (Provocations: The Spiritual Writings of Kierkegaard, 201-202)

If you know much about Kierkegaard’s biography, you’ll know that it isn’t much of a stretch to say that Jesus ruined his life. And he wouldn’t have had it any other way. May we all learn a bit more what it means to find our lives by loosing them for the sake of our Master.